Firstly, I will start off by saying these are rather general musings - I will probably (hopefully) look back on these in a month's time and think "Christ...what rubbish", so do excuse the sloppy execution and rather basic arguments!

Anyway, we first receive an in-depth description of the mere by Hrothgar, where, in a semi-hysterical speech after the death of Æschere (before Beowulf is like "grow up, buddy - it is always better to avenge lost bros than to mourn them"), he says this:

"They inhabit a hidden land - wolf-slopes, windy headlands, dangerous fen-paths - where a mountain stream flows downward beneath the cliff's mist. It is not far from here in miles that the mere lies. Over it hangs rind-covered groves - a wood held fast by its roots hangs over the water - there, each night, one may see a troubling wonder; fire on the flood, No living children of men know the bottom of that mere . . . That was not a pleasant place! From here, surging waves rise up dark against the clouds when the wind stirs up loathsome storms, until the sky darkens and the heavens weep"

(1357-67, 1372-6, my own translation)

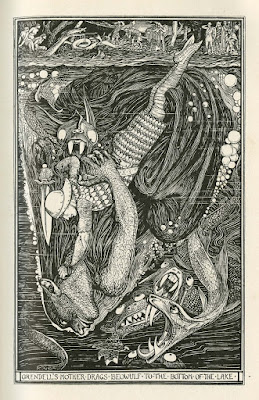

|

| Virgil Burnett's depiction of the mere |

It is a slightly confusing description - is this prime real estate by the sea (headlands, cliffs) or inland (in a forest in the mountains?). Well, it seems that where exactly the mere is, isn't necessarily the important thing, rather the nature of the mere. For one thing, if you invest in this property, you get your very own light show every night and you never have to worry about a hart jumping into your gaff.

The description of the mere has often times been compared to Blickling Homily XVI, describing Saint Paul's vision of hell (which is also reminiscent of the IRC), which, to be fair, does have quite a few similarities, including a description of water flowing down, of frosty groves, of dark mists, and also the presence of nicras or 'nicors' (immature laugh), apparent sea-monsters.

|

| Hieronymus Bosch's Christ in Limbo - Hell doesn't really look like this in the homilies, but I just love Bosch |

It has been suggested that the mere in Beowulf has some borrowed content from this homily, or at least that they had a common source - it has also been argued by Carleton Brown, however, that the Homily borrowed from Beowulf and the Visio S Pauli, as it shows shared elements from both of these, while Beowulf only shares elements with the Homily. It really depends on the dates of the two - the MS which the homilies appear in is dated to 971, while Beowulf...well, this is still and forever will be argued about, so let's not go down this fen-path. Either way, I think it is possible that Beowulf could have been a source for the homilies - it is, after all, generally agreed to be an oral poem, only written down later, so it seems conceivable that the homilist may have been influenced by the poem.

Then again, it is also somewhat agreed on that elements of Beowulf would have been added into the poem, such as biblical references to Cain and the Flood and also of course to God. Whether we choose to view the description of the mere as a later addition... well... I guess that is something that is up for debate.

A much more intriguing comparison, I think, can be made to Grettis saga Asmundarsonar, the story of a hard-ass Icelandic outlaw who loves to fight. I'll take him over Saint Paul any day!

Anyway, while these Icelandic texts date to the 13th and 14th centuries, they are based on events which occurred a few centuries beforehand. So, Grettir gets up to all sorts of antics, but most important is what happens in Chapter 66; Grettir is hanging out one day when a troll-woman enters and starts fighting with him - she (like Grendel's mother) is really bloody strong and she gets away (after getting her arm chopped off...like Grendel) and disappears down a cliff. Grettir decides to follow her down. Grettir comes to a waterfall surrounded by cliffs, and he swims beneath the current to enter a cave. He then proceeds to fight a male troll, whom he kills, and whose guts flow out of the waterfall to make a lovely bloody mess (which reminds me of Chuck Palahniuk's short story Guts), which in turn makes the priest who has accompanied Grettir to think Grettir is dead (much in the same way that Grendel's blood which is said to bubble out of the mere makes Beowulf's thanes think he is dead).

So...there seems to be an awful lot of comparisons here. Could the mere in Beowulf be a waterfall? The surging waves and the mist rising up to darken the sky could well be the mist rising from a waterfall. The churning waters which are described both when Grendel returns to the mere after his fatal fight with Beowulf and after his corpse is decapitated could merely (pun intended) be the churning waters of a waterfall. And similarly, Beowulf swims downwards to reach a dry cave - much like he would have to swim beneath a waterfall's current to reach behind (or you know, walk around or through the water as they do in films...).

Of course, problems must also arise with this comparison, especially the countries of origin (Iceland vs England/Denmark) and the dating of these stories. It is possible that it is rather from a common source or sources that these stories share their similarities. And this is something I am going to have to explore in more depth (pun intended).

|

| Henry Justice Ford - Andrew Lang's Crimson Book of Fairy Stories |

But what about the sea-monsters and the fyr on flode.....I'm going to end this one on a cliff-hanger (again, pun intended), and write about those things in a future post!