"Unchallenged, mainstream film coded the erotic into the language of the dominant patriarchal order" (835)

Women in classical cinema are looked at and displayed, and connote "to-be-looked-at-ness", while men are the "bearer of the look". Woman is spectacle, but her presence works against the development of the story, and therefore narrative, that which is propelled by the man.

Mulvey notes that the woman on display simultaneously acts as both erotic object for the characters within the film, but also those without, namely the spectator. The spectator often shares his view with the male in the film (see image above) but not always; the device of the show-girl "allows the two looks to be unified technically without any apparent break in the diegesis" (838). On top of this, "the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification", and so, he is most often the one who controls the narrative, and forwards the story. The male protagonist becomes the spectator's surrogate, and his appeal is related back to the perfect, powerful, complete "ideal ego conceived in the original moment of recognition in front of the mirror" (838).

Because of this identification with the male star of the film, when the women eventually falls in love with the protagonist and possesses her, "the spectator can indirectly possess her too" (840).

However, the female figure possesses, in psychoanalytical terms, a deeper problem in that she stirs up anxieties regarding castration due to her lack of a penis. In order to rid themselves of this anxiety, the protagonist must either control her (through demystifying her - devaluing her, punishing her, saving her) or through fetishising her (often through close ups and fragmentation of her - making her completely an object, and therefore powerless). Of course, the problem here lies in the Freudian theory that women are obsessed with the lack of a penis, which, I personally do not think is true (I don't dwell on it at least!). But, we can still view this in terms of power, cocks aside.

So, where does Beowulf come into this? Well, with Grendel's mother of course.

Looking at Zemeckis's Beowulf as a whole (as well as the Anglo-Saxon poem), the main story focuses on the titular character of Beowulf and his heroic deeds. Unlike the poem, however, Zemeckis's film introduces women as extremely sexualised figures, most notably Grendel's mother. While the 2007 film also introduces us to the character of Ursula (Beowulf's mistress, and seemingly another female figure for Beowulf to have sex with, as opposed to doing much in terms of narrative development), Grendel's mother is where we can really see Mulvey's theory in play.

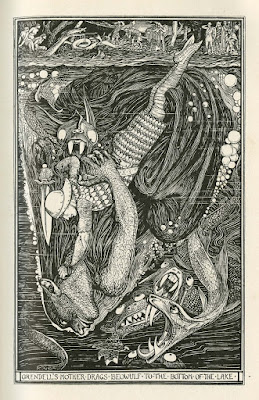

If the above image does not connote "to-be-looked-at-ness", then I don't know what it does. Everything about Grendel's mother's figure is spectacle (and spectacular), from the voluptuousness of the CGI'd body (which is actually the body of model Rachel Bernstein - adding an extra layer of objectification here) to the gold paint and the stiletto-ed feet (very Anglo-Saxon).

Grendel's mother acts as both erotic object for the male gaze within the film (Beowulf) and for that without - the audience, which is made up mostly of teenage boys (its target audience), begrudging Anglo-Saxon scholars, and students panicking the night before their Old English literature exams. As with Mulvey's show-girl conjuncture, these two views are unified when Jolie walks towards both Beowulf and the audience simultaneously (as in the above image). On top of the already-implemented threat that she poses, the extra anxiety of castration comes into play, and is played with in the film. While Mulvey puts forward two options of escape for the male; control or fetishisation, neither of these options appear in Beowulf. Rather, Beowulf gives in to Grendel's mother's temptation - it is obvious that she is the one in control - and this is further emphasised in the image of Beowulf's strategically placed sword and its melting, a sequence which can be understood as both ejaculation and castration.

This castration motif brings to mind scenes from I Spit on Your Grave (1978), above, where the heroine, Jennifer, seduces one of her rapists and castrates him in the bathtub The only difference here (as well as in Litchenstein's 2007 Teeth) is that the protagonist is female, and the castration actually happens (severed penis and all in the case of the latter!).

As the film plays out, we are reminded of the ultimate power being in the hands of Grendel's mother. However, she is still presented to us as an overtly sexualised figure, one which is no doubt meant to be an object of erotic desire for members of the audience. And while she is the ultimate winner here, she is not ever depicted as a positive figure, but rather manipulator, and as the big bad female seducer who will mess up your life and turn your children against you. In this way, she remains a sexual object and spectacle, but one which, as with Anita Sarkeesian's 'Evil Demon Seductress', may simultaneously be hated, and some of this hatred appears to come from the fact that the audience have identified with the wronged male protagonist.