I have (just about) survived my first week of tutoring Old English to second years, and....well, let's just say, I had expected university students to be a bit more communicative. Instead, it appears to be a "who can hold off responding the longest" competition. Am I just paranoid?....am I just stoned? If only I could go back to the times when listening to a Green Day album was the most productive thing I did in a day.

Whilst trying to maintain my sanity, the rest of my life must go on (my life being thesis, sleep, painting, thesis, sleep, staring into space, thesis). And the other thing my life appears to revolve around...Grendel's mother. Again?! Yes, again.

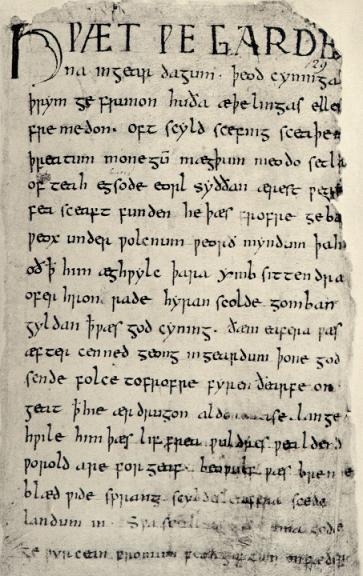

grendles modor ides aglæcwif

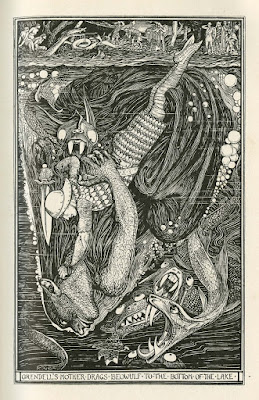

Today, I ask 'why'. Why has Grendel's mother been turned into the "monstrous ogress" with the "talons" and the wolfish ways and the gold paint and the scales and the everything?

I have pretty much established that she was not demonised by the poet himself, not even her actions (see previous posts!). Not even Beowulf and Hrothgar think she's doing something terrible. The only people who do think that, are the translators and scholars who decided

secg means "warrior" for Beowulf, but shit, look, it's also used for Grendel's mother... eh, it probably means "creature" in that instance. Just put down "creature"...or I know, I know, "monster". Yeah, that's as accurate as we're gonna get here.

So, I recently started delving into this a bit deeper, wondering who the hell is the bane of my existence (and at the same time the reason I'm doing a PhD in this subject...thank you), and, well, I guess there's a few possible reasons.

The most obvious of these is that, firstly, she is the mother of Grendel, and is therefore assumed to be monstrous. Whether or not Grendel is as monstrous as he is assumed to be, this is not enough proof for his mother to be monstrous. Secondly, she is an antagonist, therefore is bound to get the short end of the stick (is that the phrase?? Hard end of the stick? The ugly stick?) when it comes to translating her.

Be

rit Åström argues that the reason for her characterisation, and for other women's dismissal, lies in the fact that in the 1800's (when Beowulf was first given much attention), history was viewed in a linear fashion - meaning that, in their opinion, the centuries got progressively more civilised. The Anglo-Saxon era then, must have been all about power, glory, and manstuff, meaning that female figures in history got ignored because they were presumably unimportant to the Anglo-Saxons.

I think

Åström was on the right track here - after all, for a period that treated women so horrendously,

of course women were treated even worse by the Anglo-Saxons. I can picture a Victorian scholar musing over how much they'd progressed in their treatment of women in that 800 year gap. "Sure at least we're not as bad as those old Anglo-Saxons! Edith, get me some tea, woman!"

But there's most likely more to it than that. After all, the Victorian era was pretty renowned for its sexism, its lack of women's rights, and its strict confines to what femaleness meant.

Being a time of staunch Christian belief and conservative morals (carried on from the Middle Ages), the bible was a pretty big reference book on how to behave. Unfortunately for women, the bible is also a pretty misogynistic text.

Which are you?

And basically, when it comes to the bible, really only two kinds of women are prevalent. You can choose to emulate the Virgin Mary, submissive, willing to carry God's child (even though they hadn't even gone on one date yet - sluuuut) or you could emulate Eve, the one who overstepped the boundary and went against God's will (the patriarchy, man!). You can only be one or the other. You're either all good, or you're a FUCKING WHORE.

For the Victorians, this Virgin-Whore, Madonna-Eve complex was present, especially for middle and higher class women (while the working class made shit in factories and spoke in strong cockney accents according to TV). But it was probably more present in an angel-demon dichotomy. For some strange reason, in the 1800's, the ideal woman started to be seen as an angel - whereas before this, angels were muscled, androgynous figures with spears (or freakishly muscular babies). The ideal woman's role revolved around marriage and childbirth and the homestead and shutting the fuck up. And somewhere along the line, the terms 'angel' and 'domesticity' seemed to become almost synonymous, as Auerbach argues (in

Woman as Demon). This possibly started with Coventry Patmore's poem "The Angel in the House", which was basically “a

convenient shorthand for the selfless paragon all women were exhorted to be,

enveloped in family life and seeking no identity beyond the roles of daughter,

wife, and mother” (Auerbach, 69).

And so, those women who were not the ideal, who were not submissive and domestic, were often to be seen as monstrous (not necessarily

Alien or those terrifying things from

The Descent (shiver) type monstrous) or often were described with imagery harking back to the Fall, categorising them as snake-like. Basically, unfeminine actions like physical exertion and having an opinion made you monstrous.

Furthermore, a 'discipline' that was very popular in the Victorian era was that of physiognomy - basically, the assessment of someone's character by their outward appearance. Fierce scientific stuff, really! Yet its impact appears throughout Victorian literature (and still somewhat today), in works of Dickens, Brontë, Wilde, Austen, and more, and was also influential on art. Even if you look at old illustrations of suffragettes, they are often characterised as ugly women (who probably couldn't get a man anyway - why does this sound familiar! Still!). Bad guys were, and still are, often made to look like bad guys. And women who did not fit the ideal of the angel in the house (prostitutes, spinsters, feminists, female authors, fallen women), were often illustrated as ugly

Physiognomy in 19th century illustration - maybe the guy on the left has a fiery temper, harhar.

So...what the hell did these moral crusaders do when it came to Grendel's mother and translating her for a modern audience? Well, they could not have that blasphemy going unchecked (A woman? Fighting? Killing? Never!), so the easiest way to deal with it is *BAM*, tell everyone she's a monster and make her reaaaallly ugly!

Who knows if she was actively changed or subconsciously believed to be representative of a monster anyway? Perhaps a bit of both? Don't ask me anyway.

This is something I hope to immerse myself more in, and at the end of the day, it's all a bit of guessing and a bit of speculation. Any other opinions (opposing or otherwise) are very welcome.