It is with a hangover and a huge lack of sleep that I want to express what a wonderful time I had at my first conference.

I was somehow roped in to speaking at the From Eald to New conference ("and he never forgave, and he never forgot") which took place at the weekend and spent months before having "Oh christ, no" thoughts whenever it came to mind. However, as of yesterday morning, I don't have to panic again (until the next time).

It was a brilliant experience, I got to meet Hugh Magennis, Heather O'Donoghue and Rory McTurk told me they really liked my paper and I made an eejit of myself in front of Chris Jones! Everyone was absolutely lovely, and I don't think I've spent so much time laughing in a long while, especially at Greg Delanty (a true Cork man), at Niamh's and mine Beowulf fan fiction ideas (Beowulf loves Grendel) and at terribly bad and funny jokes in Tom Barry's and stumbling in my front door at 7am. There was wonderful poetry and equally wonderful papers (even if half of it did just go over my head) and a really great translation workshop by Greg Delanty, Michael Matto and Lahney Preston-Matto, where I realised I have not a poetic atom in my body.

My paper went surprisingly okay (it didn't go according to my dream the night before at least!), and I am now glad (yet also very sad) that it's all over. But at least we have decided to go to Kalamazoo next year (and not just because of the swinging that we hear goes on).

Showing posts with label translation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label translation. Show all posts

Sunday, 8 June 2014

Tuesday, 1 April 2014

Can translation ever convey the original adequately?

My simple answer is....no!

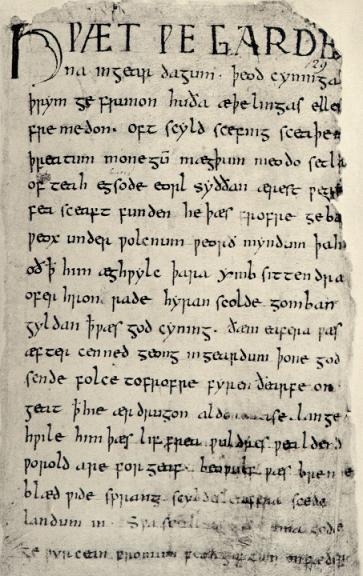

I think the whole range of translations, along with the articles about these translations, even for Beowulf alone, is proof enough of this. Of course, nobody ever knows when it's a language like Old English, and until someone invents a time machine and returns to the Anglo-Saxon era, then we never will, and even then, it would still be impossible to truly convey the exact meaning and feel of the original. And who knows how much you'd even learn when the most readily available drinking source was ale.

When reading translations of modern literature, like Haruki Murakami or Mikhail Bulgakov, I actually spend a lot of time thinking how I will never know if this is how the author wanted to convey it exactly (so deep)...and I know it can never be perfect, for the simple reason that languages are different and have different sounds, and cultures are different and have different meanings and values. The English translation of Norwegian Wood, for example, is beautifully written, but it's not going to sound anything like the Japanese. How can I know myself, that that is what Murakami wanted to convey exactly. This is especially true for works that put a lot of emphasis on words and use particularly poetic language - yes, we can recreate the alliteration, but then we lose the exact meaning - so which do we pick - we lose something in the end. When I read translations, I often think that yes, this is so-and-so's ideas and story, but it's not necessarily their language. Does that ruin these books for me? Not really, but it is something that is in the back of my mind. First world problems, eh?

As Jay Rubin, the translator of Murakami's English publications states: "When you read Haruki Murakami, you're reading me, at least ninety-five percent of the time". And at that, Rubin has the advantage of being able to discuss translating with the author, whereas for things like Beowulf, we can't exactly phone up the scribe and ask him "what exactly did you mean on line 1294? Oh, is that so? Cheers lad, nice one". Imagine how more accurate Beowulf translations would be if the author was still alive? And yet it would still not be able to accurately convey everything because, at the end of the day, if we can't accurately translate a godamn author who is alive and living in the 21st century (even if it is Japan, and we all know how weird Japan is), then what hope do we have? Nada. And at least if we want to read the 'most accurate' translation of Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita or Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, we can look up the hundreds of threads and blog posts about it, and yet, even when that language is still in use today, we can still never be satisfied.

I think the whole range of translations, along with the articles about these translations, even for Beowulf alone, is proof enough of this. Of course, nobody ever knows when it's a language like Old English, and until someone invents a time machine and returns to the Anglo-Saxon era, then we never will, and even then, it would still be impossible to truly convey the exact meaning and feel of the original. And who knows how much you'd even learn when the most readily available drinking source was ale.

When reading translations of modern literature, like Haruki Murakami or Mikhail Bulgakov, I actually spend a lot of time thinking how I will never know if this is how the author wanted to convey it exactly (so deep)...and I know it can never be perfect, for the simple reason that languages are different and have different sounds, and cultures are different and have different meanings and values. The English translation of Norwegian Wood, for example, is beautifully written, but it's not going to sound anything like the Japanese. How can I know myself, that that is what Murakami wanted to convey exactly. This is especially true for works that put a lot of emphasis on words and use particularly poetic language - yes, we can recreate the alliteration, but then we lose the exact meaning - so which do we pick - we lose something in the end. When I read translations, I often think that yes, this is so-and-so's ideas and story, but it's not necessarily their language. Does that ruin these books for me? Not really, but it is something that is in the back of my mind. First world problems, eh?

As Jay Rubin, the translator of Murakami's English publications states: "When you read Haruki Murakami, you're reading me, at least ninety-five percent of the time". And at that, Rubin has the advantage of being able to discuss translating with the author, whereas for things like Beowulf, we can't exactly phone up the scribe and ask him "what exactly did you mean on line 1294? Oh, is that so? Cheers lad, nice one". Imagine how more accurate Beowulf translations would be if the author was still alive? And yet it would still not be able to accurately convey everything because, at the end of the day, if we can't accurately translate a godamn author who is alive and living in the 21st century (even if it is Japan, and we all know how weird Japan is), then what hope do we have? Nada. And at least if we want to read the 'most accurate' translation of Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita or Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, we can look up the hundreds of threads and blog posts about it, and yet, even when that language is still in use today, we can still never be satisfied.

The much awaited Tolkien translation, to be released this May. Yipee

Some translators of Beowulf may decide that taking the route that recreates the metre and the alliteration is the best, most accurate way to go, others will decide that a literal prose translation is the best way to go. Others may try to find a middle-ground. But in the end, nobody is really going to give us Beowulf as it was received by the Anglo-Saxons.

No matter what way someone goes about it, there's always going to be some criticism of something being lost in the process. It can't be faithful in every single way - it cannot maintain all alliteration, all metrical idiosyncracies, all syntax etc, while still maintaining the most accurate and literal translation of the language itself. As a French critic once said, translations are like women, they can be beautiful or faithful, but not both (certainly, he was full of crap). As a female, I like to think of beautiful but unfaithful translations as the Jude Law's of translation.

And even if there was some way of doing this, we still cannot understand the poem how Anglo-Saxons would have. We simply don't have the same culture or beliefs anymore (although maybe if you lived in one of those modern day Viking communes in Norway you might have a better understanding!). A good example, as John D. Niles points out, is the problem of the word cuþ, "known". He asks "how can a translator express the emotive force" that this word had "for an Old English speaker, who seems to have viewed the unknown as something terrifying and who placed exceptional value on the comforts of familiar surroundings". For a culture that (most likely)believed in dragons and panotti and blemmyae, the "known" had a completely different significance!

Even if we think of this issue from an Irish point of view and look at Irish writers like Flann O'Brien (Brian O'Nolan) for instance, whose writing has a particularly Irish feel about it (the syntax, the humour). Is it possible for another culture to 'get' it as much as an Irish person would 'get' it? I'm not so convinced.

And even if there was some way of doing this, we still cannot understand the poem how Anglo-Saxons would have. We simply don't have the same culture or beliefs anymore (although maybe if you lived in one of those modern day Viking communes in Norway you might have a better understanding!). A good example, as John D. Niles points out, is the problem of the word cuþ, "known". He asks "how can a translator express the emotive force" that this word had "for an Old English speaker, who seems to have viewed the unknown as something terrifying and who placed exceptional value on the comforts of familiar surroundings". For a culture that (most likely)believed in dragons and panotti and blemmyae, the "known" had a completely different significance!

Even if we think of this issue from an Irish point of view and look at Irish writers like Flann O'Brien (Brian O'Nolan) for instance, whose writing has a particularly Irish feel about it (the syntax, the humour). Is it possible for another culture to 'get' it as much as an Irish person would 'get' it? I'm not so convinced.

Good feckin' luck to ya

Niles, John D. “Rewriting Beowulf: The task of Translation.” College English 55.8 (1993): 858-878. Print.

Tuesday, 9 July 2013

Sympathy for Eve

One of the texts I found really interesting when doing my undergrad was the Old English Genesis, especially the Genesis B section, because of its pretty unusual and unconventional depictions of God, Satan and Eve when compared to other accounts of the fall of angels and the temptation of Adam and Eve, both from the Anglo-Saxon period and other eras.

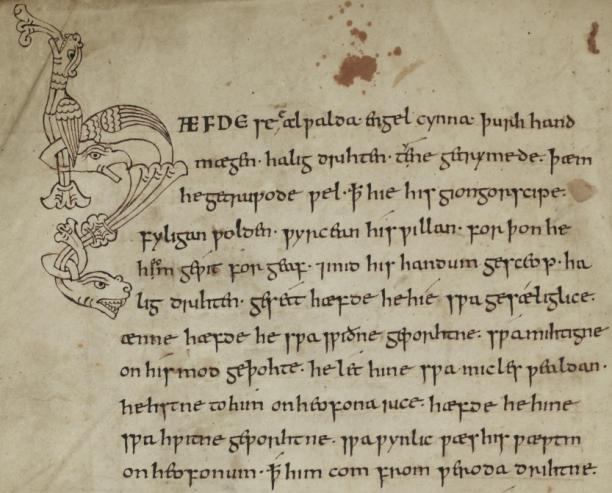

The Old English Genesis (A and B) can be found in the Junius 11 manuscript (also referred to as the Caedmon Manuscript), dating to about 930-1000AD. This manuscript also contains Daniel; Exodus; and Christ and Satan. The Old English Genesis is a translation (or transliteration when talking about Genesis B) of an Old Saxon version of the text.

As an example of this poem's unconventionality (is this even a word?), here is an example of one of Satan's soliloquies:

‘There

is no need at all for me to have a master. I can work just as many

marvels

with my hands.I have plenty of power to furnish a goodlier throne,

one

more exalted in heaven.Why must I wait upon his favour

and

defer to him in such fealty? […]So it does not seem to me fitting

that

I need flatter God at all for any advantage. No longer will I be

his

subordinate.’ – Genesis B 278-291

Reading this, Satan seems to be coming across with some fair points, right? Seems like a sound enough guy! And to further top this off, the fact that God throws him and his followers into hell like an angry toddler, kind of makes us think again about who the good guy is...and why is he being such a dick?!

So that leaves us to move on to Eve, who gets off really lightly compared to other depictions of her. Rather than damning her, the poet seems to offer her a lot of sympathy, almost going out of his way to express how it wasn't her fault:

Yet

she did it out of loyal intent. She did not know

that

there were to follow so many hurts and

terrible

torments for humankind because she

took

to heart what she heard in the counsellings

of

that abhorrent messenger; but rather she thought

that

she was gaining the favour of the heavenly King - Genesis B

Most importantly, this

pleading for Eve's lack of blame veers toward heresy. In Genesis B, it is not

out of disobedience, but of of "loyal intent" and innocent ignorance

that Eve eats the fruit. This would suggest that the poet seems to be almost disagreeing with God's judgement and punishment of her and basically we've all been suffering because of God's lousy judgement of her.

nom nom nom

Of course, it's nice that the poet is being all sympathetic towards Eve (and the Devil), but it must also be said that he is also a bit of a sexist...or more than a bit. Throughout Genesis B, Eve is described as being

"lovely" and "beautiful", yet her intelligence is never

commented on, while Adam is described as "self-determined" and is

clear-sighted and independent enough to see through the 'messenger's' (in this version, Satan sends a messenger to tempt Adam and Eve, rather than go himself) temptations. So basically, what he's trying to say is that Eve is lovely and all, and a sight to look at, but basically, the lights are on, but nobody's home. Eve, like all of our sex, has "the frail mind of women" and does not think to question the angel/serpent, but takes the apple without too much thought. Lastly, the idea of

"woman as beguiler of man" is evident here, as Adam, who can't resist Eve's "lovely" facade, gives in and takes a bite of the apple - don't you know, (warning, sarcasm alert) men can't help themselves when they are confronted with a sweet face, or a short skirt. Anyway, Adam pretty much blames it all on Eve - what a douche! This author really has us rooting for the traditional baddies!

Sunday, 7 July 2013

Grendel's Mother and translators taking the piss

Angelina Jolie as Grendel's Mother in Zemickis' film

This post is going to be like an episode of Scooby Doo, where Grendel's Mother is chasing you around, with her talons and her big ugly head, and then she takes off her monster costume and you realise it's all cool, you and Grendel's Mother aren't that different from each other, and she isn't actually a monster (speaking of which, that Scooby Doo team get a lot of really similar cases).

As I pointed out previously (and if the blog title didn't give it away), I am a Grendel's Mother fan. Furthermore I believe that she isn't a monster, but a misunderstood character who has been wrongly translated into monstrosity.

Why did it happen that she has been turned into a scary, wolf-like, reptilian, troll-thing? Don't ask me, ask the translators who thought sacrificing accuracy for artistic effects or to make Beowulf more heroic or whatever other reasons, was a good idea. And unfortunately the trend has stuck, and everybody just imagines Grendel's Mother as the monster-thing without second thought.

(Disclaimer: These are my opinions. Feel free to continue thinking of Grendel's Mother as a monster....but just so you know, I secretly clench my fists at night at the thought of you)

So, basically, Grendel's Mother has been getting a hard time of it from the very beginning, starting off with translations such as John Mitchell Kemble's 1835 translation, right up to R.M. Liuzza's 2012 translation. While researching for my thesis two years ago, I did an extensive enough search in order to find just one translation that did not demonise Grendel's Mother...but nada. I realised that there was not much point in putting too much faith in any one translation, because, when it comes to ancient languages, it is pretty impossible to interpret them exactly - there will always be some leeway, and there is oftentimes no direct translations of words.

"Big Mother", a Marvel Universe character

Grendel's Mother is first introduced to us on line 1256, where she is named as Grendel's avenger and an ides, aglæcwif (a word that would haunt me for months). This term has a pretty wide variety of translations. Alexander translates it as "monstrous ogress", Heaney as "monstrous hell-bride", "witch of the sea" (Osborn), Gummere as "monster of a woman", and there are many more similar interpretations from others. Now, the thing is, Beowulf is the only text that contains the word aglæcwif. In fancy terms, it's hapax legomenon, so it can't be compared against any other texts, which is a bit of a pain in the ass. BUT, the word can be divided into its roots, aglæca and wif. Interestingly enough, aglæca, along with other compounds containing this word, is used several times throughout Beouwulf in reference to Grendel, the dragon, Sigemund (a hero of old) and Beowulf himself. When used in relation to Beowulf, it has been translated as "gallant man" (1512, Heaney), "warrior" (Gummere) and "fierce commander" (2592, Heaney). So...how do they get "monstrous ogress" and such terms out of a word that is otherwised used as "fighter, valliant warrior, dangerous opponent, one who struggles fiercely" (Sherman Kuhn)?? Does it not make more sense, and is it not a whole lot more accurate to translate it as "female-warrior" perhaps, seen as wif simply means "woman"? And although it is often used with negative connotations (eg in Juliana, when describing the devil), it has also been found in a description of Bede by Byrthferth of Ramsay, where he is called aglæca lareow, "awe-inspiring teacher" (Orchard).

It's not fair to say that the poet intended aglæcwif to have negative connotations, and it is unreasonable to translate it as "warrior" or "hero" when it comes to Beowulf, but as "monstrous ogress" or "monster woman" (Chickering) when it comes to Grendel's Mother. I will also point out that ides comes before aglæcwif, a word "always used in reference to female humans, never animals, and usually reserved for noble women” (Porter). As ides aglæcwif is the first term used to describe Grendel's Mother, it of course influences how we view her for the rest of the poem. Unfortunately, we're not introduced to her as "female-warrior" or "warrior lady", and from the very outset we are encouraged to view her as a monster. Boo.

The cover of Seamus Heaney's Beowulf translation

I won't go into so much detail on the other terms, because we'll be here all day, and I'm suffering from a truly impressive hangover and I want to go lie out in the sun like a lizard (speaking of which, I wonder if this is what Grendel's Mother in Gunnarsson's Beowulf and Grendel must do). So I'll just lay out the necessary points.

- Atolan clommum, found on line 1502, has been translated as "terrile hooks" (Alexander) and "horrible claws" (Chickering), whereas it can also be translated as "terrible clasp", which does not necessarily imply any crazy physical deviations.

- Laþan fingrum, also, which is literally translated as "hateful fingers" has been translated as "savage talons" (Heaney) and "claws" by Chickering. These people are really out to get her!

- Brimwylf, lines 1506 and 1599, has been translated as "wolf of the waves" (Gummere) and "sea-wolf" by Kemble. Although these translations aren't incorrect, brimwylf does not necessarily mean that Grendel's Mother is a literal sea wolf, or even resembles one physically. It may simply function as an epithet, which isn't so far-fetched as wulf or wylf is often seen in other cases to denote warriors...the really obvious one being Beowulf himself! "Bee-wolf" or "wolf of the bees" does not mean that Beowulf is literally a stripy, flying, wolf! Another example is in The Battle of Maldon, where the invading Vikings are called wælwulfas (96), meaning "slaughter-wolves", and likewise, we know that the Vikings weren't actually wolves, so having wulf or wylf as a name, does not mean you are a physical wolf...or that you are to be perceived negatively. In fact, the whole reason the "wolf" compound was used in general, was most likely because of an "early admiration for the wolf" (“wulf” def. I. Bosworth-Toller), and so far from being a derogatory term, it is most like that the poet was using this to emphasise her skills in battle.

- Our next word, grundwyrgenne (1518) has been translated as "monster of the deep" (Kemble), "swamp-thing from hell" (Heaney, you crazy dog), and "the abyss's curse (Morgan). It is also defined in the Clark-Hall dictionary as "water-wolf". Grund is obvious - ground, earth. But wyrgenne is where the problem lies. Wearg is defined in the Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary as “I. of human beings, a villain, felon, scoundrel, criminal . . . II. of other creatures, a monster, malignant being, evil spirit”. So...and I know many disagree....seeing as there isn't exactly any solid proof (just translations) that Grendel's Mother isn't human, the second definition just doesn't really seem solid enough. And although there may be some confusion with the Old Norse cognate vargr, meaning both "outlaw" and "wolf", it must be noted that other instances of wearg are not translated as "wolf"...so why Grendel's Mother? Exactly, it shouldn't be.

- Secg: On line 1378 this can be found, and has many colourful interpretations, like "sin-flecked being" (Gummere) and "most evil monster" (Crosley-Holland). Buuuut, secg is also used for the male characters in the poem, and guess what, it doesn't seem to mean "most evil monster" in those instances, but rather "warrior" or "prince" and even "hero"(Heaney). Sorry guys, ye gotta try harder.

- Wif unhyre (2120), literally “awful woman” is translated as “ghastly dam” (Heaney).

- Handbanan (1330), “slayer-by-hand” is translated by Alexander as “bloodthirsty monster”.

- Mere mihtig, which appears directly after grundwyrgenne, literally “mighty sea-woman” has been translated by Heaney as “the tarn hag” and by Morgan as “the great sea-demon-woman” (whut??).

- Heo (1292), which quite literally and simply means “she”, is translated as “hell-dam” by Heaney and “monster” by Crossley-Holland.

If that isn't enough proof (of sorts, seen as we can't exactly ask the poet or any of his contemporaries) then I don't know what to do.

Of course, I haven't mentioned any of the descendants of Cain hooha, but some other time I will get around to that.

Works Cited and some references for those who are interested in reading further (I'm totally just covering my ass):

Alexander,

Michael, tran. Beowulf: a Verse Translation. London: Penguin, 1973.

Print.

Alfano,

C. “The Issue of Feminine Monstrosity: A Reevaluation of Grendel’s Mother.” Comitatus:

A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 23.1 (1992): 1-16. Print.

“The

Battle of Maldon.” The Labyrinth. Georgetown

University. 2007. Web. 9 Aug. 2012.

Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary.

2010. Web. 9 Apr. 2012.

Chickering,

Howell D., tran. Beowulf: A Dual-Language Edition. Bilingual. New York:

Anchor, 2006. Print.

Clark-Hall,

J. R. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Virginia: Wilder Publications,

2011. Print.

Crossley-Holland,

Kevin, tran. Beowulf. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.

Cynewulf.

Juliana. Ed. Rosemary Woolf. Exeter:

U of Exeter P, 1993. Print.

Gummere,

Frances B., tran. Beowulf. Florida: Red and Black Publishers, 2007.

Print.

Heaney,

Seamus, tran. Beowulf: A New Translation. New ed. London: Faber and

Faber, 2002. Print.

Hennequin,

M. W. “We’ve Created a Monster: The Strange Case of Grendel’s Mother.” English

Studies 89.5 (2008): 503–523. Print.

Kemble,

John Mitchell, tran. Beowulf: A Translation of the Anglo-Saxon Poem of

Beowulf. London: William Pickering, 1837. Google Books. Web. 14 Jun. 2012.

Klaeber,

Frederick, trans. Robert D. Fulk, ed. Klaeber’s

Beowulf. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2008. Print.

Morgan, Edwin, tran. Beowulf. Exeter: Carcanet, 2002.

Print

Orchard,

Andy. Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript.

Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003. Print.

Oswald,

Dana M., Monsters, Gender and Sexuality

in Medieval English Literature. Suffolk: Boydell and Brewer, 2010. Google Books. Web. 5 Jun. 2012.

Porter,

Dorothy Carr. “The Social Centrality of Women in Beowulf.” The Heroic Age.

2001. Web. 9 Apr. 2012.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)