Having went to see The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug the other night, and only recently returning from the country of Tolkien's birth, I guess it's only natural that this post should concern him and The Hobbit's links with Beowulf. I have previously mentioned some things in a previous post, but let's make another one, sure why not lads.

Despite some dodgy CGI at times (I really can't understand how they can create such an amazing dragon, yet at times the horses look like they are taken out of Zemickis's Beowulf (see what I did there!)), and despite the fact that it will never be as great as Lord of the Rings, the film was really good. Surprisingly, I even liked the introduction of Tauriel to try and somewhat lessen the sausage-fest that The Hobbit is. And Kili, the obligatory exceedingly attractive dwarf (Ireland, I'm proud of you!). I enjoyed that part too.

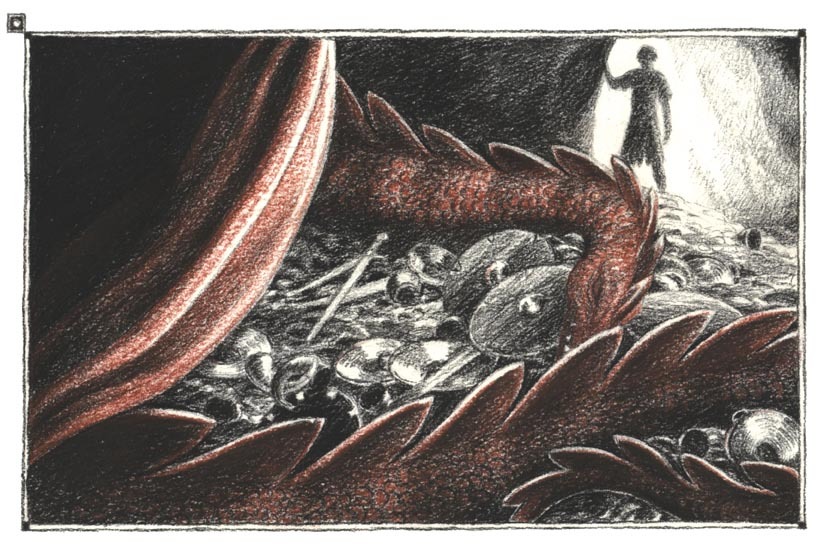

An illustration which would suit either Beowulf or The Hobbit.

It's actually from a Beowulf book by Anke Eissmann

It's actually from a Beowulf book by Anke Eissmann

The most obvious link between The Hobbit and Beowulf is of course the dragon! In a way the dragon scenes are climaxes of both stories (although The Hobbit ends with a huge battle, it's fair to say that the dragon is the big thing in the story). Most notable, I think is the fact that the dragon is woken by the theft of a cup, by Bilbo in The Hobbit, and by some other eejit in Beowulf. As well as this, both dragons' lairs are entered by a secret passage: in Beowulf "there was a hidden passage, unknown to men" (Heaney's translation), whilst in The Hobbit, the dwarves (I guess you could extend this entrance as being "unknown to men" also, seen as dwarves technically aren't men) enter by the secret passage, revealed only at a certain time - the last light of Durin's Day. After the theft of treasure from both dragons' barrows, they both go absolutely ape and enact revenge on the surrounding land - from this, we can deduce that dragons have the emotional capacity of a 5 year old child. As in Beowulf, it is not the protagonist that kills the dragon in The Hobbit, but a relatively minor (but very honourable) character - Bard. Both dragons end up in a pretty similar grave also - "they pitched the dragon over the cliff-top, let tide's flow and backwash take the treasure-minder" (Beowulf), and for Smaug; "he would never again return to his golden bed, but was stretched cold as stone, twisted upon the floor of the shallows". Sleep with the fishies.

Another thing, which I was thinking of, is The Hobbit's influence on Beowulf adaptations - it is possible that the dragon from John Gardner's Grendel was made with considerable influence from Smaug, who unlike the Beowulf dragon, actually speaks, and appears to be able to hold a pretty decent conversation!

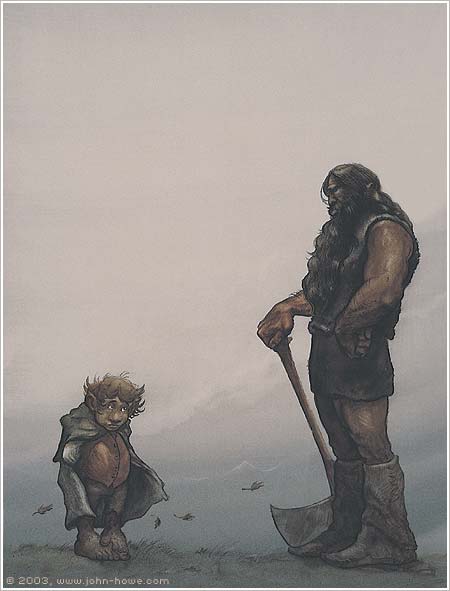

Grendel, by John Howe

Although a bit sketchy, there has been some comparisons between Grendel and Gollum. Although Gollum has a shit ton more brains and charisma than Grendel does, it is interesting to note some similarities. In Beowulf it is said that Grendel is a "grim demon", dwelling "among the banished monsters", a descendent of Cain (from Cain also sprang ogres (orcs?), giants (perhaps our friend, the cave-troll, from the Mines of Moria?), and elves...although it's pretty clear that Tolkien's elves aren't seen as Cain's clan - nobody as pretty as Legolas could be!). It is clear from both stories that both Grendel and Gollum are outcasts, both live in caves and both are pretty ugly. The point about Cain is also very interesting, because, as we learn in Lord of the Rings, Gollum, back when he was still known as Sméagol, killed Déagol (his relative) in order to take the ring. And while we know Gollum was once, many many years beforehand, a hobbit of sorts, there is also perhaps a human link for Grendel in his connection with Cain.

Numerous other links exists between both stories

Numerous other links exists between both stories

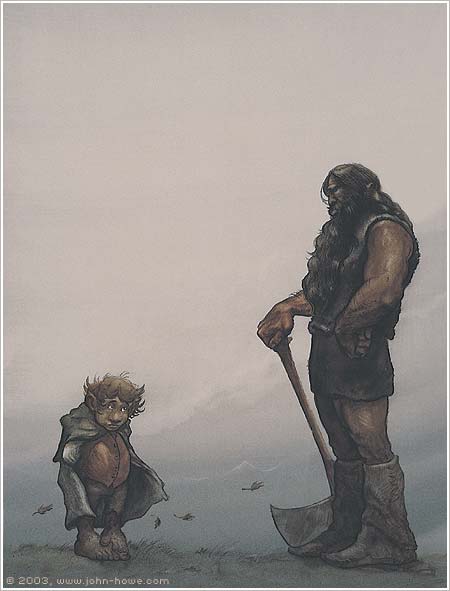

- Beorn as a reworking of Beowulf himself. Perhaps? Perhaps. Both are proud and strong. And as seems to be happening all the time in Beowulf (isn't it a surprise he had time to do all his killing!), Beorn's home is full of feasting and story-telling. Futhermore, the name Beorn can have two different meanings - "man" or "warrior" from the Old English beorn, or "bear" from the Old Norse björn. On the other hand "Beowulf", means "bee-wolf", which is a kenning for "bear"!

Beorn, by John Howe

- As in Beowulf with Hrunting, the swords in The Hobbit are given names, like Sting, Glamdring, and Orcrist, depending on their history.

- As mentioned in this blog, a parallel can be seen when the dwarves are awaiting Bilbo's escape from the goblins' cave, and Beowulf's thanes awaiting his return from Grendel's Mother's mere.

- Beowulf has 14 companions (so 15 in all). In The Hobbit, there are 13 dwarves, Bilbo Baggins making the 14th member. And Gandalf can be considered a 15th.